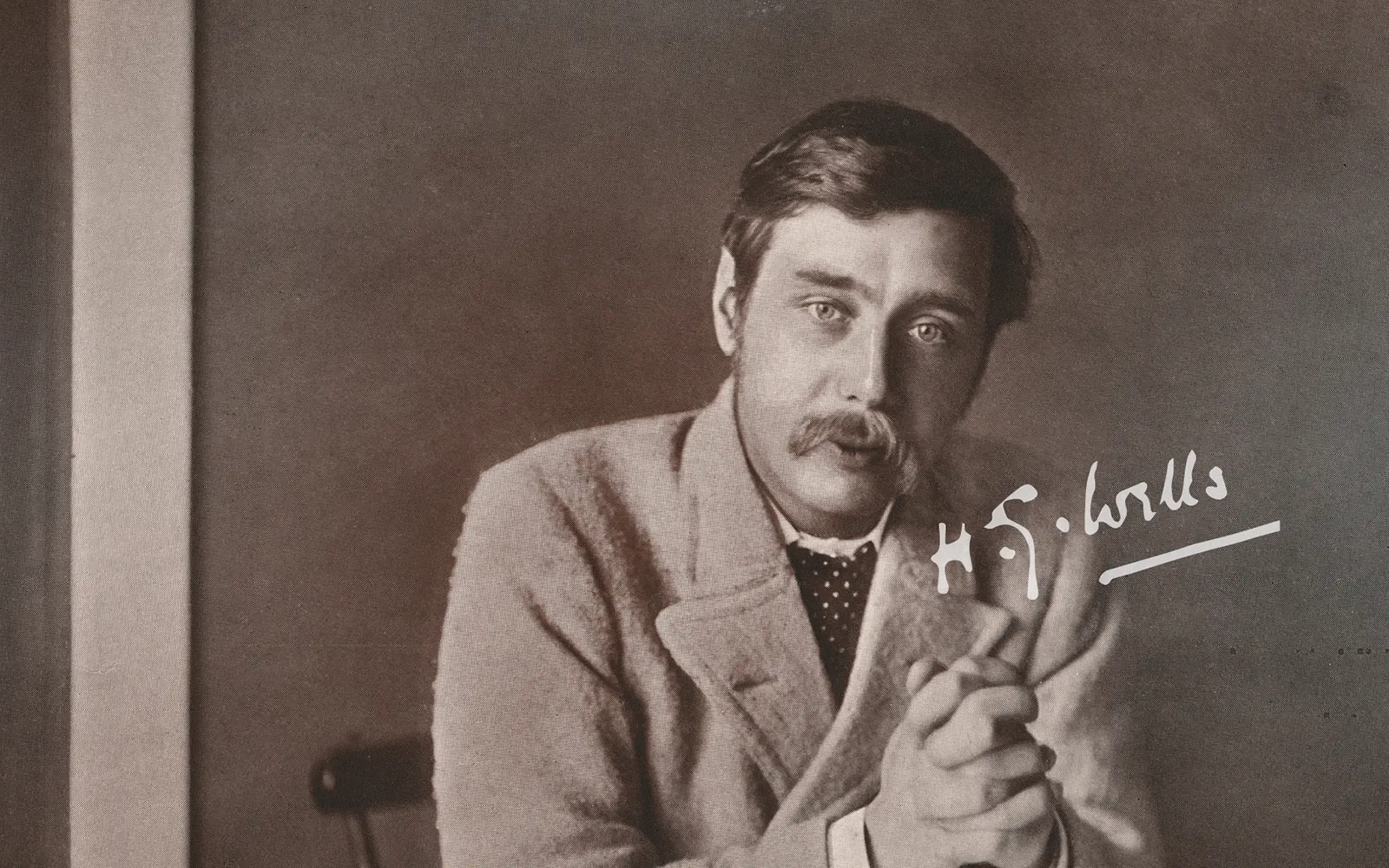

H.G. Wells: A Scientific Romance

Explore the early stories and novels of H.G. Wells, one of the major early figures in the world of science fiction.

H.G. Wells ExhibitionASC NewsletterOur Collections

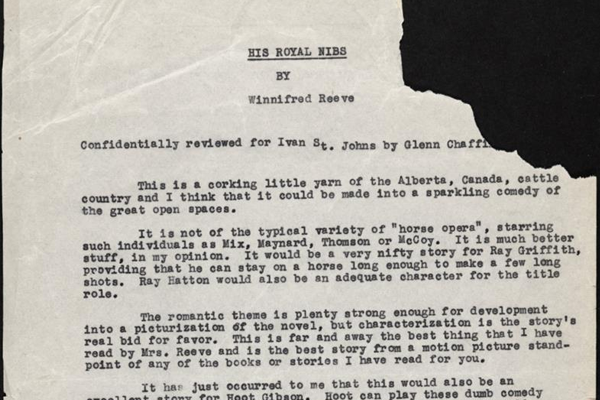

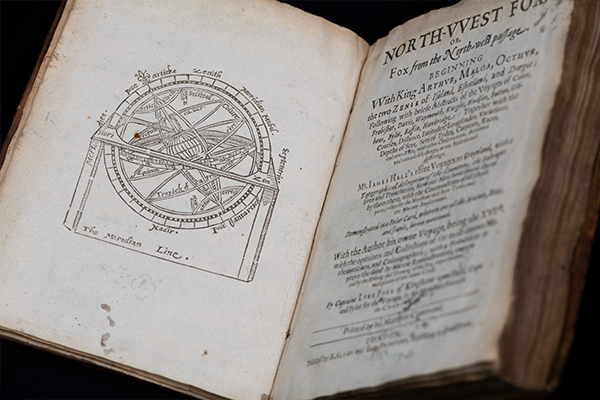

As one of Canada’s largest collections of diverse, unique, and rare materials, UCalgary Archives and Special Collections holds over 12 linear kilometres of archives as well as more than 230,000 rare and special book items. The collections at UCalgary are especially rich in materials related to the history of Calgary and southern Alberta, UCalgary history, Canadian architectural records, records related to the arctic and the north, and Canadian literary, music, and military history. Book holdings are particularly strong in popular and genre fiction, comic books, Canadian literature, and western Canadian history.

With a strong emphasis on incorporating archives and special collections into teaching, learning and research, we strive to make our holdings accessible through classroom engagement, leading primary source reference service, and storytelling through exhibitions and digital collections. At UCalgary, we prioritize the preservation of heritage alongside transformative experiences with primary sources for our communities.